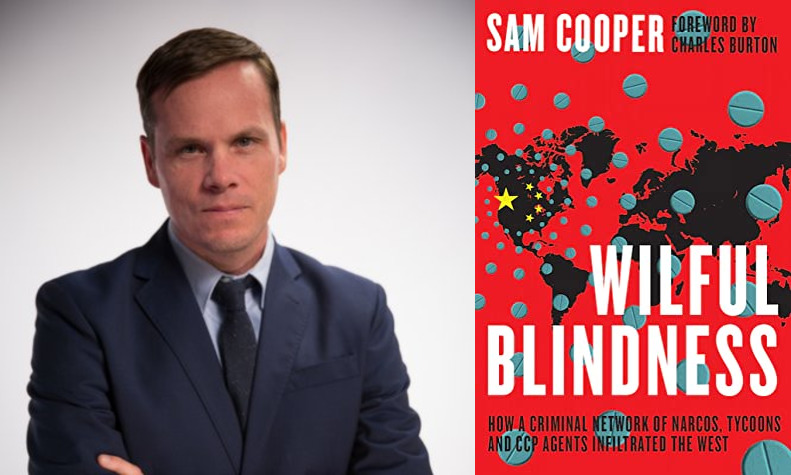

Following is a series of edited extracts from the book, ‘Wilful Blindness: How a Network of Narcos, Tycoons and CCP agents infiltrated the West’ by Canadian journalist Sam Cooper. The book will be released internationally on 20 May and has been made available exclusively to The Sunday Guardian in India. The extracts come from the chapter ‘Compromised Nodes’.

COMPROMISED NODES

Money-laundering was the shared interest in Vancouver. But something else was definitely happening. The Big Circle Boys and Chinese intelligence players had started with casinos. And they moved into real estate and finance, Canada’s soft spots for economic infiltration.

My sources had been telling me some things that I couldn’t believe until I saw the evidence myself. These were people who understood criminal intelligence and geopolitics. They talked about the convergence of organized crime and state-actors in China and Iran and Mexico and Russia. They were saying the impacts of the money-laundering that I was uncovering in Canada went a lot deeper than fentanyl deaths and soaring housing prices in Vancouver and Toronto and Montreal.

They were saying transnational money-laundering endangers democracy. It erodes the rule of law. It’s a national security threat. But you need to look deeper, they said. Look at who is standing behind the transnational criminals. More to the point, who is standing above them holding a protective umbrella. It was a frustrating situation for the people talking to me. Canada has excellent criminal intelligence. But what the RCMP and CSIS know about the Chinese Communist Party’s collusion with the Big Circle Boys and Chi Lop Tse’s super cartel never makes it to trial.

What my sources were describing was essentially a modern version of the map laid out 20 years earlier in the controversial Canadian intelligence report, Sidewinder.

And when the people who wrote Sidewinder saw my reporting on E-Pirate and Paul King Jin, it set off alarm bells. Michel Juneau Katsuya—the former CSIS Asia-Pacific desk chief—recognized the metastasized node he had identified way back in the 1990s. Gangsters, spies and industrialists covertly operating under the Chinese Communist Party.

But there were new convergences.

After 2015, my sources started seeing kingpins of the Chinese underground banking cartel brushing up against state actors from Iranian narco-terrorism networks. For example, E-Pirate surveillance records filed with the Cullen Commission showed a Mideast organized crime suspect was registered to a vehicle used in Paul King Jin’s alleged illegal casino and Water Cube spa operation. And Mideast organized crime suspects served as bodyguards for Jin and his superior, these records showed. And the Sinaloa Cartel was also in the mix. But Chinese state actors definitely ran the show, intelligence experts told me.

Money-laundering was the shared interest in Vancouver. But something else was definitely happening. The Big Circle Boys and Chinese intelligence players had started with casinos. And they moved into real estate and finance, Canada’s soft spots for economic infiltration. But Beijing has a high-tech long-game. And Vancouver was becoming a global technology node for narcos, state actors and cyber-criminals.

This was fascinating stuff, but I approached it with some caution. It sounded like a spy novel.

Part of it was my innate Canadian sense of insulation. Although I had uncovered lots of money-laundering in B.C. casinos and real estate, I had grown up with a sense that my country was a bastion of uprightness and stability. Corruption and wars and spy plots happened in other countries.

So I would nod with interest when I heard these geopolitical crime tips. But inside, I would think, this is Canada. I’ll believe it when I see it. My mind was opening, though. There were major deals happening in Vancouver that made no sense from a national security perspective. In August 2017, I wrote a story with my Postmedia colleague Doug Quan, “How a Murky Company with Ties to the People’s Liberation Army Set Up Shop in B.C.”

We explained how China Poly—a $95-billion arms trading, real estate and industrial behemoth owned by Red Princeling families—was welcomed with open arms in Vancouver. We reported that China Poly had already been accused of numerous corruption and smuggling cases worldwide. They were deeply involved in Xi Jinping’s neo-imperialist Belt and Road infrastructure projects. Their branding depicted the world as a Go board—the ancient Chinese game in which the winner occupies territory to dominate the loser. China Poly often turned up in sketchy dealings with third-world dictators and arms traders. The United States accused them of helping Iran develop its missile program.

In the 1990s, a China Poly agent in California was caught smuggling 2,000 AK-47s into the United States. While that national security probe was underway, one of China Poly’s Princelings visited the White House and got implicated in the so-called Chinagate fundraising scandal. Macau casino barons and Triad associates circled around that political influence case. Some of them were familiar names from my research of Lai Changxing’s networks. I found the Macau barons and China Poly were like hand and glove. Case in point: Stanley Ho spent millions at auction to hand China Poly an object of tremendous propaganda value.

And this bronze pig head was displayed at Poly Culture’s November 2016 “art gallery” opening in Vancouver. Our Vancouver Sun story set the scene like this.

“Under the watchful eye of Vancouver police in tactical gear, attendees admired four rare bronze zodiac heads—a tiger, monkey, ox and pig—that had once adorned the Summer Palace in Beijing.

“It was the first time these cultural relics—looted following the palace’s destruction by British and French forces in 1860—had been displayed outside China since their repatriation.

“The opening of a gallery and North American headquarters here by Poly Culture was the culmination of intense behind-the-scenes courting by local politicians—especially Liberal MLA Teresa Wat, then B.C.’s international trade minister—and was hailed in government documents as a major economic win and ‘significant day for British Columbia in its relationship with China.’”

So I could see the shadowy outlines of state actor activity that my sources were talking about. And my instinct was China chose to display the looted relics in Vancouver for propaganda value. It was like Xi’s regime was planting a flag in the West. In China, the zodiac heads represent the burning national humiliation of defeat in the Opium Wars.

But now B.C. politicians were quietly rolling out the red carpet for Xi’s Belt and Road.

Something else that was hard to believe at first was the connection between China and Mexico that my sources talked about. But I eventually found it was no stretch at all: Chinese actors in fact were merging with the Sinaloa Cartel in North America. And some extremely credible Canadian security intel sources blew my mind with this assessment: the Chinese state seemed to have influence with the Mexican cartels. They had to, one RCMP source told me. Because the Chinese underground bankers were handling almost all of the Latin American narcos’ money.

It was trade-based money-laundering on an industrial scale. Chinese merchants moved the Mexican cartel money worldwide by converting drug cash into factory goods. Merchants shipped the goods wherever the cartels needed their funds. The goods were sold. The proceeds banked. Politicians were bribed, weapons were purchased and more drugs were produced and exported. At the same time, Chinese state controlled factories were shipping mountains of fentanyl precursors into Mexican ports.

As always, it was a textbook case that enabled me to grasp the relationships. I studied U.S. government records on the so-called Chinese-Mexican whale, Zhenli Ye Gon. The Shanghai-born pharmaceutical tycoon—a Chinese national and Mexican citizen—was busted in his Mexico City hacienda in 2007. According to U.S. court records, in a secret room off Ye’s master bedroom, police found a stash of military weapons and a two-tonne pile of cash worth US$207 million. Stop for a minute and visualize that. This was a large room with U.S. dollars, Hong Kong dollars, pesos, euros and Canadian dollars neatly stacked halfway to the ceiling. It was the unlaundered proceeds of Ye’s crystal meth business. And he looked like a very connected figure in China: educated at East China University of Political Science and Law, a school administered by Beijing’s Ministry of Justice.

This was a decade before massive shipments of fentanyl precursors started to land in Vancouver and Manzanillo. But in the early 2000s, Ye was the largest chemical supplier for the Sinaloa Cartel, importing at least 50 tons of meth precursors annually from a Chinese pharmaceutical company. His case had the markers of the Vancouver Model written all over it. He was using Mexican currency exchanges to transfer hundreds of thousands of cash per week into HSBC bank accounts. He was wiring the money into Nevada. In just three years, he gambled at least $125 million in Las Vegas, U.S. court records say, betting $150,000 per hand at baccarat. And Ye was on such good terms with the Venetian Sands—operated by Venetian Macau owner Sheldon Adelson—that the casino comped him a Rolls-Royce, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Meanwhile, I learned the U.S. government had started to pay attention to my reports about China’s growing real estate footprint in Vancouver. I was informed that some in the U.S. State Department worried that Chinese transnational crime was establishing a North American beachhead in Vancouver.

But the RCMP and CSIS appeared to be overmatched. Canada had no real counterpunch to answer China’s sophisticated financial activities in Vancouver. And so, there was a growing FBI and DEA presence in British Columbia. To me, it seemed like Canada’s sovereignty on the west coast was gradually eroding. At least a little bit. And you could see the concern with Xi Jinping’s so-called Belt and Road projects, the type of Chinese infrastructure investment deals warmly accepted by tin-pot dictators in underdeveloped nations. I knew these deals were being pitched to B.C. Liberal premier Christy Clark’s government in 2016, when Clark and Wat met with Chinese Communist Party officials and real estate tycoons in Guangdong and Hong Kong. And B.C.’s government eventually greenlighted a $190-million Belt and Road import-export centre in 2018.The first of its kind in North America.

This despite the fact the U.S. State Department believes Belt and Road projects are a major vector for Chinese espionage and trade-based money-laundering, according to my Canadian intelligence sources.

THE GENERAL

My personal ‘This cannot really be happening in Canada but indisputable evidence says it is’ moment came in late 2017. This was after I started to break E-Pirate stories. Sources I had never heard from started to contact me. One source told me I should look at a compound east of Vancouver and near the U.S. border that was filled with stunning wealth. They said the River Rock Casino whale that owned this hacienda in Chilliwack appeared to be involved in unimaginable money-laundering. In a vast underground bunker, the whale had dozens of high-end luxury and military vehicles stacked on hoists. There were red Ferraris, black Rolls-Royces, white Mercedes, green military jeeps. It was a parking lot of horsepower that would have made El Chapo blush. But what really shocked me was the photos of the high-roller’s industrial collection. There was a red and gold fire truck, a big rig truck, and vintage rocket launchers and ground-mount machine guns.

I was informed the bunker’s owner—a tall, square-jawed and handsome man—was called the General by his followers in Vancouver. And indeed, WeChat videos showed that when Rongxiang “Tiger” Yuan relaxed in his compound’s karaoke lounge to drink fine liquors and sing odes to the Motherland, he wore his military fatigues. Despite my efforts to question Tiger Yuan about his many documented ties to Paul King Jin, I have never been able to reach him directly. So I can’t ask him why RCMP investigators refer to him as “Suspect 2” in confidential documents that name many alleged River Rock VIP gamblers and loan sharks, including Paul King Jin, who is identified as “Suspect 22.”

Through his lawyers, Yuan has denied any involvement in criminality and he sued for defamation after my reports for Global News outlined what my sources and RCMP and B.C. Lottery Corp. investigation records say about him. Yuan says he is a successful businessman who has been an active member of the Chinese-Canadian community for many years, and he meets many individuals.

When you see an elite People’s Liberation Army veteran allegedly involved in massive B.C. casino money-laundering and dealing with the most violent of Mainland China narcos and loan sharks in Canada—and very active in Beijing’s political influence operations in Vancouver—to me it suggests problems worth investigating.

I knew the RCMP and CSIS were watching the General in B.C. But across the country in Ottawa leaders seemed completely oblivious. And I had information that screamed for national attention. Sources told me an Iranian national named “Kousha” was the ‘meatshield’ for Tiger. Canadian deportation records showed this tattooed bodybuilder had a criminal record. In one case, Kousha was convicted for threatening to kill a Vancouver police officer. He had racially abused the officer and his family, and announced he “hated Jews so much that he smiled at their pain, knowing that he could cause fear.” A confidential RCMP link chart indicated Kousha was an employee of “Kenny”—the young Chinese man who shadowed Tiger in public and stored restricted weapons in Tiger’s compound. And photographs from inside Tiger’s compound showed Kousha posing with his finger on the trigger of a German MP40 submachine gun.

So why was Rongxiang Yuan surrounded by gun-toting thugs but also tight with Chinese consular leaders? I had to understand what this convergence of state actors and organized crime suspects meant for Canada’s security. So I consulted international experts like Jonathan Manthorpe, Alex Joske and Clive Hamilton in Australia, and Professor Anne-Marie Brady in New Zealand to understand President Xi Jinping’s so-called magic weapon of espionage and political interference, the United Front Work Department.

By 2020 I had seen enough to eradicate my doubts. My sources were correct. And Canadians had to be informed.

KHANANI AND THE RCMP MOLE

But I also knew that a national money-laundering inquiry was needed. Reporting from Ottawa, I was finding the Vancouver Model was a Canada-wide problem. Transnational drug cartels running underground banking supernodes in China and the Middle East were deeply intertwined with real estate and trade in Toronto and Montreal as well as Vancouver.

And it was a sprawling DEA investigation that ultimately helped me understand how RCMP corruption was enabling organized crime to advance across Canada.

I first learned of the Five Eyes probe of Altaf Khanani and Farzam Mehdizadeh in October 2017. I was waiting to speak to financial professionals about my E-Pirate reporting at a conference in Toronto.

A lawyer for Great Canadian Gaming had emailed, warning me not to deliver my speech. I ignored the baseless libel threat. Canadian bankers wanted to hear me talk about a serious threat to the nation. But I have to admit I was a bit distracted. That was until Doran flicked up a slide showing the mug shots of Khanani, a Pakistani national, and Farzam Mehdizadeh, a 57-year-old Toronto currency exchange owner. When Doran said the men were Five Eyes targets I scrambled to turn on my tape recorder. This meant the powerful Western intelligence alliance viewed these men as serious national security threats.

Doran explained that RCMP units had tailed Mehdizadeh driving from Toronto to Montreal and back 81 times in a single year. The RCMP had been watching Mehdizadeh since at least 2015. Montreal is still superficially dominated by the Italian mafia. But Middle Eastern and Chinese underground bankers increasingly handle the drug money in Montreal, a vital port for narco routes up and down the eastern seaboard.

On March 9, 2016, the RCMP got a warrant to take Mehdizadeh down for international money-laundering. At 10:25 p.m. on April 17, he was speeding back from Montreal on Highway 401 when Ontario Provincial Police pulled him over in Quinte County, near the Sandbanks Provincial Park on Lake Ontario.

He didn’t seem very surprised.

“He voluntarily disclosed he has a large sum of money in his possession…in the amount of $1.3 million,” an RCMP investigation affidavit says. The RCMP said Mehdizadeh had laundered $100 million in Toronto and Montreal in just one year.

But there was so much more to the case.

I found the RCMP only knew about Mehdizadeh because of brilliant work from the DEA and Australian federal police. RCMP’s intelligence directors were briefed in October 2014 at the DEA’s secret headquarters in Chantilly, Virginia. There were dozens of investigators and analysts from the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Since 2008 DEA had been running undercover agents into Hezbollah narco-launderers’ cells in Medellin, Dubai, Panama City. Agents discovered a web of businessmen just like Mehdizadeh collecting drug cash for Iranian state-sponsored criminals in cities worldwide: Toronto, Vancouver, New York, Los Angeles, Sydney, Paris, Melbourne, Miami, London. The DEA broke the case by infiltrating the top of the pyramid. They said Altaf Khanani was the mastermind who washed $16-billion per year for Latin American Cartels, Chinese Triads, Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Indian narco-terrorist Dawood Ibrahim, and Hezbollah. It was Khanani’s ties to Iran and Hezbollah that worried the DEA the most. Police called him the Goldman Sachs of underground banking. Not an exaggeration, considering Khanani’s network reportedly handled 40 percent of Pakistan’s foreign currency exchange.

The DEA had no idea at the time but they should have been equally worried about Khanani’s Canadian ties. I would eventually learn that Khanani and Mehdizadeh’s hawala network allegedly had protection from Canada’s most powerful police intelligence official, alleged RCMP mole, Cameron Ortis.

Extracted from:

Book: Wilful Blindness: How a Network of Narcos, Tycoons and CCP agents infiltrated the West

Author: Sam Cooper

Publisher: Optimum Publishing International, Montreal/Toronto

Pages: 472